History

Tamina plot, courtesy of Heritage Museum of Montgomery County

Light green represents Tamina In 1871. The dark green shows its size today.

Grogan Cochran Lumber Company placed their mill west of the railroad tracks. Photo courtesy of Heritage Museum of Montgomery County.

Logs being loaded onto a tram loader for transport back to a mill. Notice in the lower section of photo that the tracks are portable. Photo courtesy of Heritage Museum of Montgomery County.

Speedy Pak was one of the first stores in the area, providing provisions to the lumber industry workers. Photo courtesy of Randy Woods.

Cover photo of "Where Do I Go," a book written by John Elmore about his constant desire to learn more about the world and its people. Photo courtesy of Wanda Horton-Woodworth.

Elmore Family on their porch ready for church. Photo courtesy of Wanda Horton-Woodworth.

John Elmore was the first Negro mail carrier in Montgomery County. His sister, Mary Louise Williams, was a midwife in Tamina and for the Grogan family. They both lived into their 100s. Photo courtesy of Wanda Horton-Woodworth.

Photo courtesy of Wanda Horton-Woodworth.

Portrait of those baptized in the lake on what is now Research Forest Drive in The Woodlands. Wanda Horton-Woodworth in in this picture. She was eight year old. Photo courtesy of Wanda Horton-Woodworth.

Four generations of the Randle family. Descendants of Julia Randle (Aunt Julia) and Willie Lee Randle gather at the home of Rheade and Ruth Amerson (Aunt Julia's daughter). Circo 1990. Photo courtesy of Wilmeter Amerson-Haynes.

Jaren Chevalier has fond memories of watching and playing basketball with his dad, Reginald. Photo courtesy of Jaren Chevalier.

Tamina Tabernacle Church eventually split into two churches: Falvey Memorial Baptist Church and Lone Star Baptist Church. This photo shows the congregation in front of Lone Star Baptist Church with the Reverend WJ Jones (pictured far right). Image taken approximately 1956. Photo courtesy of Wanda Horton-Woodworth.

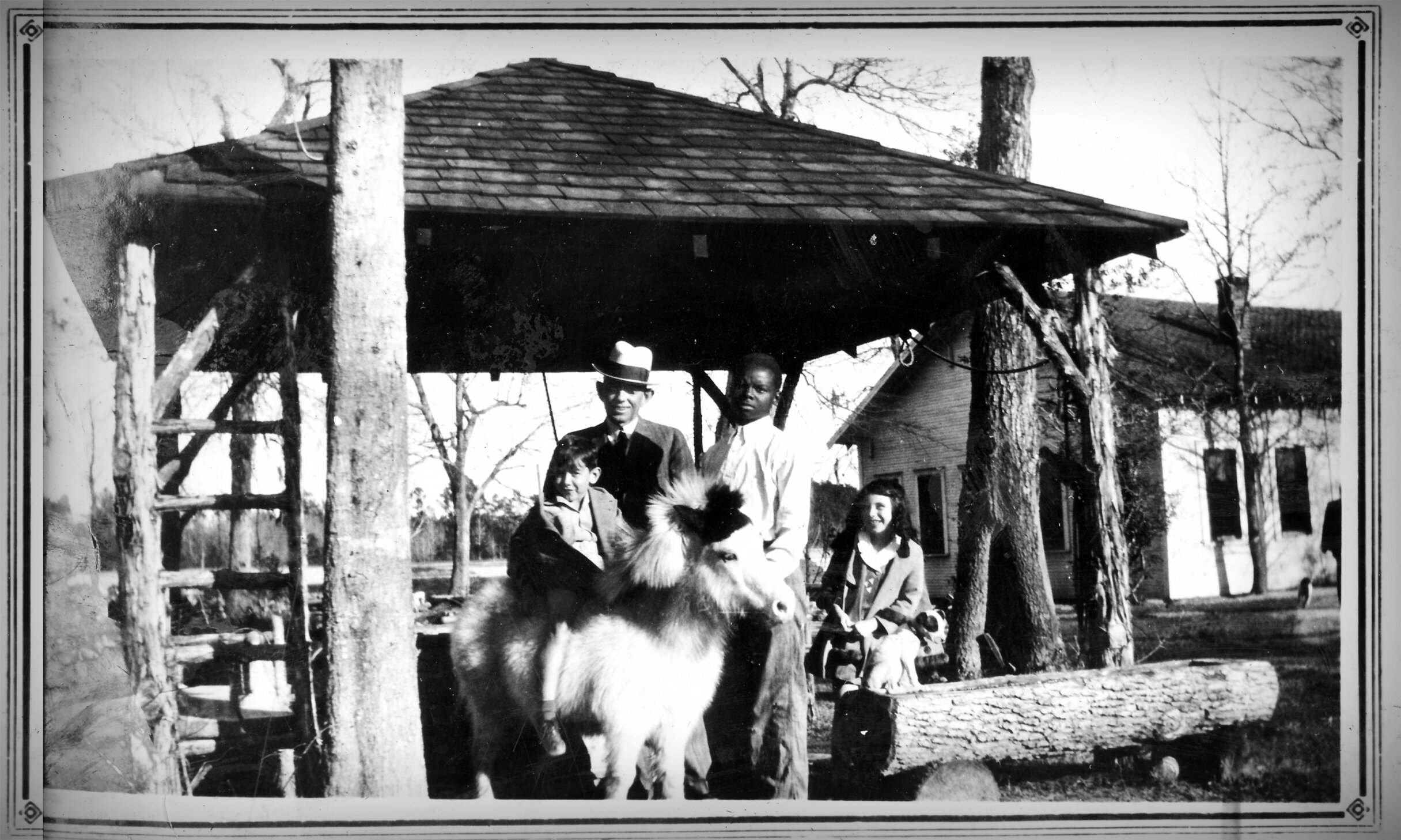

Dr. Falvey spend his holidays on his property in Tamina. Photo courtesy of the Gravis family.

Dr. Thomas Seymour Falvey. Photo courtesy of the Gravis family.

Dr. Falvey family members and boy from Tamina enjoy the lake by Falvey's summer house. Photo courtesy of the Gravis family.

The funk band, Exit, is probably best known for their release, "The Little Green Monster." Photo courtesy of Johnny Jones.

Johnny Jones, the second from the left, helped serve during Dr. and Mrs. Hayes' parties with his brothers and sister. Photo courtesy of Johnny Jones.

Ollie Mae's father, Flang Pierson. Photo courtesy of Ollie Mae and Joe Rhodes.

Ollie Mae's mother, Olivia Pierson. Photo courtesy of Ollie Mae and Joe Rhodes.

Barry Schuster and Ranson Grimes ready for their annual trail ride. Photo courtesy of Barry Schuster.

This photo was taken by Marvin Zindler's team, which came to help Tamina get a water system in place in the 1970s. Photo courtesy of Joe Rhodes.

Tamina lies just east of Interstate 45, ten miles south of the city of Conroe and 32 miles north of Houston.

Today, Tamina is a small, unincorporated town in southern Montgomery County, Texas, encompassing less than a square mile of land. As told by the town’s elders though, Tamina once covered a far greater area, reaching north to Minnox (a town once located just south of Conroe), west to Magnolia, east to the San Jacinto River, and south to Halton (just north of Rayford) when it was established in 1871.

This freedmen’s town’s landscape has a unique charm, reminiscent of long summer days in the country. Several churches line the main street that runs parallel to Missouri Pacific Railroad tracks. Hundred-year-old live oaks shade homes, and horses can be found behind wooden fences or tethered to trees.

While some roads are paved, most remain dirt-based and covered with gravel. There are no sidewalks. A few homes have recently been built, but most are simple wooden structures put up in the mid 1900s, many of which are in disrepair.

There are a handful of businesses, including a tree service and cement company. But this quiet southern town presents a striking contrast to the thriving communities and cities hedging its borders — The Woodlands, Oak Ridge, Chateau Woods, and Shenandoah — all of which were built on land which was once Tamina.

When slaves were at last given their freedom, the vast majority became sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and day laborers. Fewer than two percent of freedmen had money to purchase land. The families who established what was first referred to as Tammany in 1871 were among this minority.

Tammany was an ideal location. It was far from other towns, property could be purchased inexpensively, and there was work to be found in Montgomery County’s growing logging industry. The founding families built homes, churches, a one-room school house, and a general store. They raised hogs and tilled their own land. Gradually, the town’s name changed to Tamina, though many residents continue to use the original pronunciation.

While Tamina remains a rural place with small-town values, its residents are surrounded with opportunities only larger cities can offer. Their children now attend some of the best schools in the country, employment opportunities surround them, entertainment and cultural events are a stone’s throw away, and the faith-based and outreach-service community in the surrounding areas are available to offer assistance. They lack the infrastructure needed for them to thrive though and face the threat of gentrification.

Tamina is one of the last remaining freedmen’s towns in the United Sates.